The Amazon is the cornerstone of life in Latin America. Its ecological importance is reflected in the availability of water, forest services in carbon capture, and the richness of its flora and fauna. It is home to various indigenous peoples whose existence is directly linked to the ecological balance and biological cycles of the forest, among other things. The Amazon is the axis of life and the epicenter of conflicts associated with development models and legal and illegal economies that draw their income from the predation of areas of high environmental value.

Deforestation is an open wound in the heart of the Amazon: over the last two decades, Latin America has lost 55 million hectares of forest, according to the latest information (Silveira et al., 2022). A large proportion of these hectares have now become pastureland for cattle, monocultures or unplanned urban zones. Much is being said about the Amazon, and resources are pouring in to protect it, but unluckily, several governments have come and gone, sitting back to watch the forest burn after lighting it on fire, including the governments of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Guillermo Lasso in Ecuador and Ivan Duque in Colombia.

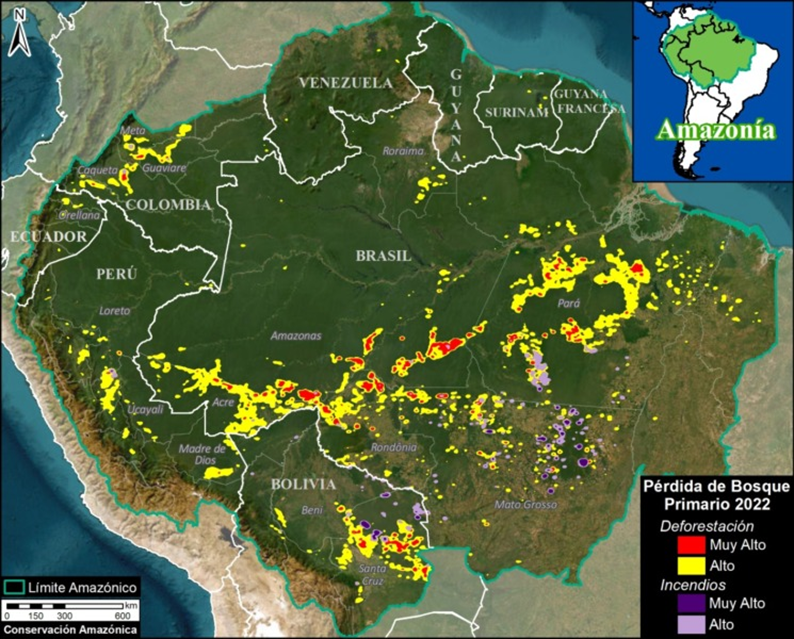

Map 1. Fires and deforestation in the Amazon Source: https://www.maaproject.org/

It's a well-known fact that national borders have never been drawn on the basis of connectivity between ecosystems, but rather have fragmented environmental regions left to drift by the will of each government on its own side of the border. In this case, eight countries are territorially involved in a suite of Amazonian ecosystems, and in dividing an ecological structure of such magnitude, it depends on the will of each country to conserve the biological and cultural diversity that floods this region. i Against this backdrop, in the 1970s a cooperative body was set up to chart a common course between these countries, recognizing that the national scales of environmental policy were insufficient to curb the threats facing the Amazon, and through the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) a process was initiated that remains unfinished after more than forty years.

In August 2023, after 14 years, the ACTO Presidents' Summit was held, and once again there was no response to the possibility of sharing a diagnosis and a plan for the Amazon between popular governments - such as Lula in Brazil, Arce in Bolivia or Petro in Colombia - and neoliberal governments - such as Lasso in Ecuador or Boluarte in Peru. This may be explained by each government's representation of the Amazon biome. For a government like Bolsonaro's, the Brazilian Amazon was the world's largest source of forest products, and this defined its management style (Deutsch and Fletcher, 2022). By contrast, for a government like that of Evo Morales, the Amazon was an indigenous territory and the lungs of the earth (Gautreau and Bruslé, 2019). The divergence of these visions leaves the Amazon without a common, integral roadmap. With the triumph of Lula in Brazil and Petro in Colombia, the door is once again open for a joint environmental management model for the Amazon, but also the possibility of a vein attempt in the face of regional mafia sabotage, private interests, climate change denialist governments and US intrusion.

Political context

The political correlation of different forces in Amazonia presents us with a demanding panorama. Without delving too deeply into the specific characteristics of each government, we could say that the equation is as follows:

Guyana has a government considered to be center-left, led by President Irfaan Ali of the Parti populaire progressiste/Civique (PPPC). Surinam is governed by the liberal Chan Santokhi, with his Progressive Reform Party (VHP), which has declared itself the defender of the specific interests of the country's population of Indian origin. Brazil finds itself with a new government led by Lula Da Silva, which is showing signs of renewal in its approach to global conflicts, but at the same time is tolerant of major capitalist investment in the country. Bolivia's government, meanwhile, is led by Luis Arce, who is attempting to retrace the democratic path after the Bolivian right-wing coup d'état that caused Evo Morales to step down in 2019. Arce and Morales are part of the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS), although a rift has recently formed between the two leaders.

Ecuador recently elected Daniel Noboa as president to complete Guillermo Lasso's presidential phase. Heir to one of Ecuador's wealthiest families, Noboa is leader of the recently formed neo-liberal National Democratic Action party. In Peru, the situation is critical due to President Dina Boluarte's betrayal of the government program with which she had won as Pedro Castillo's vice-presidential running mate. Boluarte has crafted a repressive, neoliberal government, hand-in-hand with Peru's old political class. In Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro's Bolivarian government enjoys relative stability and faces an electoral process scheduled for 2024. Lastly, in Colombia, a progressive government led by Gustavo Petro is making headway, strengthened in its environmentalist grammar.

Source: https://www.radionacional.co/

In short, eight countries, five progressive governments, three reactionary governments and tension over the place of Amazon ecosystems and peoples in regional integration. However, in the light of history, the formula has not been so simple, as right-wing governments have carved up the Amazon while progressive governments have restored it. The most striking case in point is the attitude of Ecuador's Citizen Revolution government, led by Rafael Correa, towards the Amazon rainforest and the environmental movements that have mobilized to protect it. Despite declaring his concrete intention to maintain the integrity of the ecosystems of Yasuní National Park, Correa ultimately gave in to the temptation to extract oil in the heart of the jungle, triggering not only a war between indigenous communities, but clearly betraying the mandates that his own government had raised to constitutional level in terms of the rights of nature and Buen Vivir.

A correlation of forces with a progressive majority is useful for the Amazon and the success of ACTO. However, this correlation has not yet translated into a regional model of environmental management. This is due, among other things, to the strong influence exerted by actors such as the US Department of Defense's Southern Command, which continues to claim to conduct environmental policies in the Amazon as part of an apparent military cooperation that, in any case, has always operated to the detriment of the sovereignty of Latin American countries and ecosystems. Added to this is the contradictory policy of openness that leaders such as Gustavo Petro have put in place by inviting the United States to form a “Special Military Force for the Amazon”, while Southern Command has bluntly declared that its interest in military deployment in areas of environmental interest in Latin America corresponds strictly to resources likely to feed the US economy, such as “the lithium triangle, oil resources and 31% of the world's fresh water”.ii

Contradictory visions

The ACTO presidents' summit concluded without a common path for the Amazon, in the absence of the presidents of Venezuela, Ecuador and Suriname. The progressive majority in the correlation of forces for the Amazon region was not matched by any eventual coincidence in confronting threats such as deforestation, legal extractivism, illegal economies or the accelerating loss of biodiversity. For example, while Gustavo Petro's government, as part of the aforementioned fight against deforestation, celebrated the American contribution to the militarization of the Amazon through a donation of UH-60 helicopters to the Colombian policeiii, Luis Arce (president of Bolivia) declared, at the Belém summit, his explicit rejection of the imperialist militarization of the region, the advance of which is presented in the form of NGOs whose environmental work is apparent.

On the issue of deforestation, it was impossible for the Summit declaration to end with anything other than vague phrases, unrelated mentions of “sustainable development” and the 2030 Agenda. No concrete targets were agreed to tackle this scourge, with the Bolivian government particularly reluctant to talk about zero deforestation because of the “limits to achieving it”. On the other hand, when it comes to mining and hydrocarbon extraction in the Amazon, Gustavo Petro's government has remained virtually alone in defending the idea of a regional moratorium, in the face of doubts from Brazil, Venezuela and Suriname, whose oil reserves and search for new deposits on the bangs of the jungle determine the prudence with which they steer clear of any agreement in this area.

Another point of disagreement, but one that was recorded in the declaration, concerns the financing by the Global North of an ambitious Amazon restoration program. Lula Da Silva insisted on this point, even proposing the figure of one hundred billion dollars a year for environmental cooperation for the Amazon. Gustavo Petro was highly critical of this, declaring that, in his opinion, “asking for money is not enough. It's a rhetorical way for the North to say it's doing something. If we value the Amazon, it's worth a lot more. We're not going to get there with a gift from the North. Dina Boluarte, President of Peru, limited her interventions to proposing a transnational marketing strategy between all countries to promote sustainable development in the Amazon.

In the end, the declaration that emerged from the Presidents' Summit was all environmental rhetoric and no concrete actioniv. Basically, these are debates which, although linked to the regional correlation of forces, are explained more by the adherence of the vast majority of progressive and popular governments to the extractivist consensus in Latin America. In the face of this, it is the social movements that continue to press for progress for the Amazon and its indigenous peoples. Proof of this is their proactivity in working groups and protest spaces just days before a Summit of Presidents of the Amazon Treaty, historic in that it had not been held for 14 years, and which remained short on vision, at least for the time being.

Original version (in spanish) : La Amazonía sin rumbo y bajo fuego

i Colombie, Brésil, Bolivia, Pérou, Équateur, Surinam, Vénézuela y Guyane

ii “Estados Unidos ni disimula sus intereses en América Latina”. Page 12. 23 janvier 2023. Voir ici: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/517903-litio-petroleo-y-agua-dulce-estados-unidos-ni-disimula-sus-i

iii Voir ici: https://x.com/LuisGMurillo/status/1718043950261358647?s=20

iv Declaración Presidencial con ocasión de la Cumbre Amazónica – IV Reunión de Presidentes de los Estados Parte en el Tratado de Cooperación Amazónica. Voir ici: https://petro.presidencia.gov.co/Documents/230809-Declaracion-Presidencial-con-ocasion-de-la-Cumbre-Amazonica.pdf