April 28th, 2021 will be forever remembered in History as the beginning of the “Paro Nacional”, a large-scale national mobilization in Colombia. History will remember that this “Paro” for its inspiring resistance, but also for its 80 dead (Indepaz), its nearly 300 disappeared and its torture centers in grocery stores.

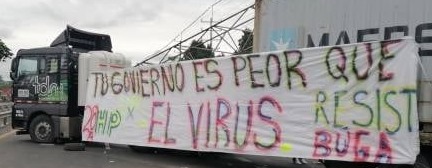

The protests, that lasted more than 8 weeks, remind us of the strikes that occurred in the 70’s. In Spanish, the word paro, which means stop, coexists with the word strike, huelga, describing a workers’ labour stoppage in one or more sectors of the industry. The 2021 Paro has been characterized by roadblocks in rural areas next to indigenous reserves, in collective territories of afro-descendant communities and in areas where the campesino organisations are the local authority. But above all, that Paro’s been marked with urban mobilizations unprecedented in the last 50 years of social struggle, which is rare in Colombia.

Much has been said about the role of youth, most of whom come from peripheral and marginalized neighbourhoods within major cities where they built barricades and defended the neighbourhoods using first line tactics. The First Lines are to the Latin American present what the black bloc was to the years of counter-summits and other mobilizations against the capitalist globalization. Much more colourful, they are composed of dozens, if not hundreds of young people, often wearing bike helmets and shields made of barrels cut in half, defending the first line. These barrels are colored with graffities which read ACAB, 1312, Ni una menos and other slogans that characterize the current social struggles.

The role the youth is perhaps the element that has generated the biggest consensus, both on the left and the right, and in the face of the necessity or offering a response to the failure of negotiations with the trade unions, the government has adopted this analysis of the facts by proposing elections to youth counsels and youth integration programs. Although this combative and colourful youth was the international emblem of its mobilizations, it was not alone, supported by a cohesive social community that was solidified by the creation of improvised medical brigades, even including improvised community clinics in order to avoid arrest in case of hospitalization, soup kitchens organized by the mothers if this youth, as well as campesino, afro and indigenous blockades, which have had their own first lines for decades, called “guard” (guardia indígena). The indigenous, afro and campesino guards represent the core of protection for the non-armed, self-governed communities. The first lines are in some ways a new type of urban guarding system, but still in its early stages.

In July 2021, after 8 weeks of protests, the indigenous guard went to Bogotá to perform a ceremony with the first lines of the Portal of Resistance aware of the fact that this type of popular organization must be structured and conscious of its role of community protection in a country that’s been at war for so many years. The Portal of Resistance is one of the dozens of places that have been renamed during this struggle where the debunking of the statues of colonial conquerors in the hands of indigenous peoples, including the Misak, has been intertwined with inauguration ceremonies that have renamed streets, avenues, bridges and squares : Bridge of a Thousand Struggles, Portal of Resistance, Endurance Road, etc. A movement that is aware that a page is being written in History with a capital H takes time to leave its mark in peoples’ memories.

The Portal of Resistance is one of the dozens of places that have been renamed during this struggle where the debunking of the statues of colonial conquerors in the hands of indigenous peoples, including the Misak, has been intertwined with inauguration ceremonies that have renamed streets, avenues, bridges and squares : Bridge of a Thousand Struggles, Portal of Resistance, Endurance Road, etc. A movement that is aware that a page is being written in History with a capital H takes time to leave its mark in peoples’ memories.

The antecedents of this struggle are numerous: in 2008, in the midst of the war, the indigenous movement declared itself as a Minga, collective action for the common good, and walked from the south of the capital, bringing together over the course of the days many social and community organizations and that joined the ranks of the indigenous peoples who, in their words, decided to risk dying in their feet rather than on their knees. Student movement made headlines in 2011 with the MANE, a national alliance that shook the country, sending thousands of students into the streets. In 2013, the free trade agreements and their devastating effects on the campesino economy and its very existence while its seeds were being privatized that gave rise to the first of a long series of Paros agrarios (agrarian) – 2014,2016,2018 – leading to a negotiation process with the national government in parallel with peace negotiations with the guerrillas, the FARC and ELN. As for the FARC, the agreements signed with these agrarian and popular sector actors were not fulfilled, as with the ELN, the negotiating table was eventually deserted by the government.

In 2019, the Colombian social movement seeking to create alliances between the rural, student, union and urban sectors issued a call for mobilization which surprised with its vigor, forcing the government to enact curfews that were systematically defied by hordes of neighbours wielding pots and pans.

The global pandemic of COVID-19 disrupted this upward curb, with slogans such as “stay home”. A slogan imported from the North in a country where the majority of people leave their homes to ear their daily bread as workers in the informal economy, and where respecting sanitary measures means starving. While the state financed airline companies risking bankruptcy, the little money meant for the food baskets for the poorest neighbourhoods was diverted, leaving thousands of people hungry.

As early as June 2020, symbolic mobilizations of a few hundred marches alerted international attention as red rags, symbols of hunger, were displayed in the windows of homes across the country. In September, the tone rose following a public scene of police brutality when Ordoñez, a law student and taxi driver, was tased and beaten to death by police. His offense was drinking a beer on a public road. The videos show the victim screaming asking the police officers to stop while he was dying went viral. Just a few days before, in the suburb of Soacha, around ten youths had died when the local police station caught on fire. Three days of riot followed the release of the Ordoñez footage.

As early as June 2020, symbolic mobilizations of a few hundred marches alerted international attention as red rags, symbols of hunger, were displayed in the windows of homes across the country. In September, the tone rose following a public scene of police brutality when Ordoñez, a law student and taxi driver, was tased and beaten to death by police. His offense was drinking a beer on a public road. The videos show the victim screaming asking the police officers to stop while he was dying went viral. Just a few days before, in the suburb of Soacha, around ten youths had died when the local police station caught on fire. Three days of riot followed the release of the Ordoñez footage.

The tension continued to rise and sporadic mobilizations to resume until April 2021, where a true social explosion seized the opportunity of a unitary union mobilization to blow away everything that seemed to prevent the world from changing. Indeed, during this month, a tax reform was implemented in order to increase taxes, including those of basic products such as chicken, coffee, chocolate, sugar, salt and more. The citizens were the ones targeted by these new taxes while the economic and politic oligarchy was spared.

Then, 8 weeks of paro. The scenes of horror, of torture, of death, finally succeeded in slowing down the popular assemblies in neighbourhoods, as well as the barricades and roadblocks. However, that episode marked the consciousness. The pandemic acted at first as a cover, making invisible the rumbling anger, but then it became a catalyst for ever increasing unrest.

It is now the turn of the elections, youth counsel elections in 2021, then the parliamentary and presidential elections in 2022, to act as a lid on this anger that has not subsided.

A progressive coalition is on the march and an alternative candidate has a chance to take the presidency for the first time in history, but whatever the outcome of these elections, the landscape that follows is uncertain and likely to be turbulent.

Will an alternative government face a coup attempt or at least destabilization by the United States and the military and paramilitary forces it has trained, as in Peru a short time ago or in Bolivia and Honduras, to name a few recent examples? And if it can govern, will this government be able to substantially improve the living conditions of the population in an economy dependent on global markets and the whims of capital? What will be possible to transform in a country where improving working conditions, for example introducing the 8-hour day or a minimum wage that would allow people to eat, not to mention unemployment insurance, seems to be an anti-capitalist program when it is only a matter of liberal social gains?

The elections of the youth councils did not have the enthusiasm expected by the government, the war continues to rage and to massively displace populations such as the hundreds of Emberás of the Chocó region who have taken refuge in a park in the center of Bogotá, facing daily risks of eviction by the riot police, while they only claim the right to return to their territories in peace. This story will be written soon, nourished by the hopes accumulated in this National Paro that allowed us to believe, even if only for a moment, that anything was possible.